Child’s Play: Developing the Architecture of the Brain

October 30, 2019

“But for children, play is serious learning. Play is really the work of childhood.”

The benefits of playtime begin at birth but will last a lifetime.

While adults might find fulfillment from their 9-to-5s, the best way to look at play is not by thinking of it as something squeezed in between meetings, meals, and bedtimes, but rather as a child’s job — albeit, a fun one. As Fred Rogers said, “Play is often talked about as if it were a serious relief from learning. But for children, play is serious learning. Play is really the work of childhood.”

As CEO of the recently revamped Louisiana Children’s Museum, Julia Bland has dedicated her career to creating a New Orleans institution that supports play in its many forms.

“Play is critically important,” she says. “It develops the whole child: mind, body, spirit.”

First 1,000 Days …

According to UNICEF, the first 1,000 days of life — from birth to age 3 — is critical for overall health, growth, and neurodevelopment. Play is an important element of this time, Bland says, in developing the “architecture of the brain.”

“It’s important, starting at birth,” she says. “The kind of play varies, and has tremendous value in connecting, attaching, and bonding. The infant is developing a foundation of trust in their caregivers, which allows the child to then build upon the social-emotional foundation in healthy development.”

While playing with a 3-year-old sounds easier to accomplish than with a newborn, and more fun, it’s just as important. Parents, especially new parents, may not know how to play with their new baby. Simply playing peek-a-boo, singing and talking, and even narrating everyday chores is play.

Talking to infants might feel silly, but Bland cites a 1995 study from the University of Kansas that found words matter, big time. After observing the interactions of 42 families with infants from different socio-economic backgrounds over a three-year period, researchers found that 86–98 percent of the words used by each child by the age of 3 were derived from their parents’ verbal interactions.

But the kicker isn’t exactly what words were used, it’s how many each child heard, which varied greatly along socio-economic lines: Children from low income families heard about 616 words per hour, while those from working class families heard around 1,251 words, and those from professional families heard roughly 2,153 words.

But the kicker isn’t exactly what words were used, it’s how many each child heard, which varied greatly along socio-economic lines: Children from low income families heard about 616 words per hour, while those from working class families heard around 1,251 words, and those from professional families heard roughly 2,153 words.

The disparity in this family conversation played out as all children reached third grade, paralleling a significant gap in educational achievement. The more words a child hears, the better they’ll be at building pre-literacy skills — vocabulary, print awareness, letter knowledge, narrative skills, and phonemic awareness. A playful approach to building these early literacy skills include signing, rhyming, storytelling, puppetry, and reading, Bland says.

While the amount of interactive conversation is just one challenge to a child’s healthy development, screen time is another. Too much is not good, but what about educational programming disguised at entertainment?

“While the content might be educational, it’s not a solid replacement for tangible, child-directed play,” Julia says.

… And Beyond

Older children also benefit from the power of play — they discover their own interests and passions while sharpening skills like social behaviors, problem solving, processing emotions, communication, and collaboration. A child may find that they have a love for a specific activity like creating art or dramatic play, building structures, or caring for an animal.

Bland recalls a recent conversation she had with a woman visiting the Louisiana Children’s Museum. The woman said that it was just a two-hour visit to the museum, specifically the grocery store, as a young girl on vacation that led her to return to New Orleans ten years later to study the culinary arts at Tulane University.

“This was a pivot point in her life,” Bland says. “We frequently hear that these childhood experiences lead to actual careers.”

Bland points out that parents play an important role in this, too.

“When parents observe rather than watch, they would start to understand what [their children] are passionate about, how they learn, and how they think,” she says, which parents can then build tailor-made play experiences around.

“When parents observe rather than watch, they would start to understand what [their children] are passionate about, how they learn, and how they think,” she says, which parents can then build tailor-made play experiences around.

Intramural sports and after-school enrichment programs could also be considered play — they arguably help develop passions and social skills — but can sometimes contribute to the overscheduled child, counteracting what child-directed play is all about.

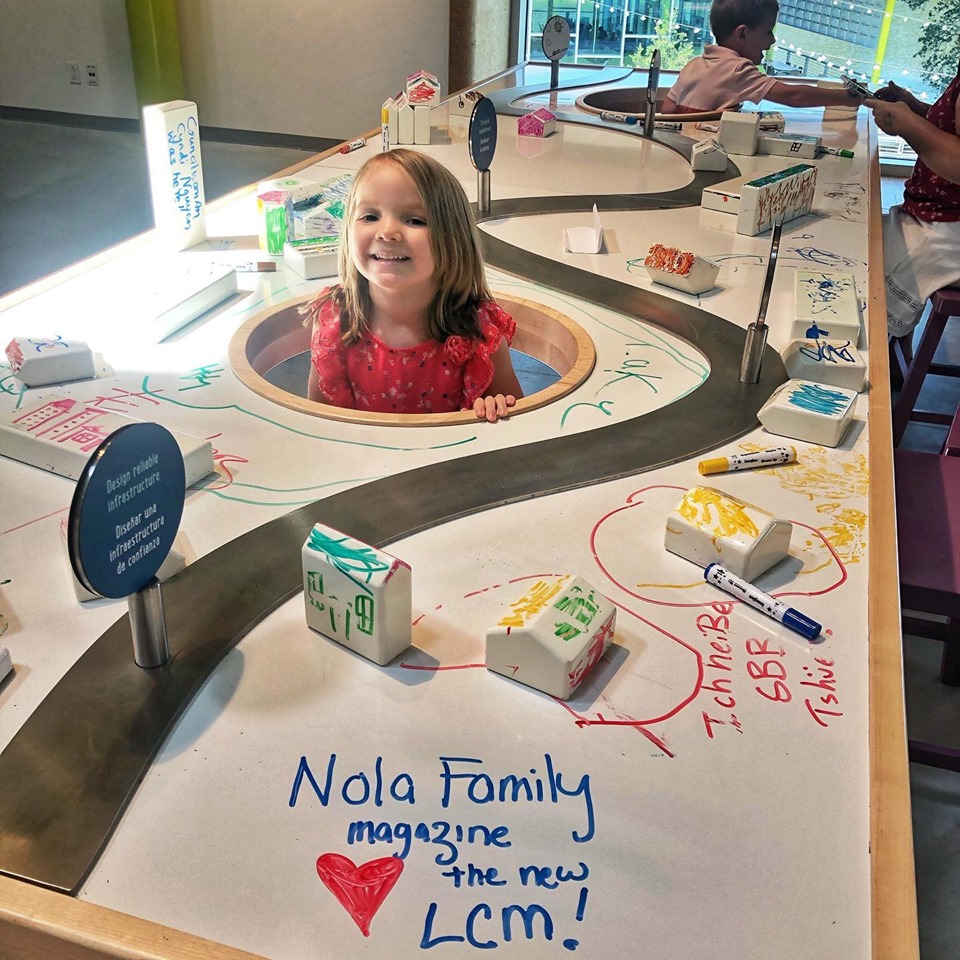

Child-directed play is a guiding principle of the new Louisiana Children’s Museum. The move from its former location on Julia Street to its current spot in City Park earlier this year allowed museum leadership to rethink learning and play and how to foster both. The initial inspiration came from focus groups of young children who were asked to help design the museum’s new exhibits.

Bland admits that there’s no right or wrong way to play. No special tools or expensive toys are needed. Sticks can build a nature fort, pots and pans can become musical instruments, and folded paper can become a fleet of airplanes.

When children “clock-in” for playtime, and are able to commit to it like a 9-to-5, they aren’t compensated with a salary, but with essential life tools that’ll help create passionate, resourceful, collaborative adults.

Tim Meyer is managing editor of Nola Family magazine.

Tim Meyer is managing editor of Nola Family magazine.